Quantitative easing, tightening and why they matter

Quantitative easing (QE) is an unconventional form of monetary policy in which a central bank purchases financial assets, mainly government bonds but also other securities. This expands the central bank’s balance sheet, increases the money supply and market liquidity, and reduces longer-term yields. QE supports the economy by lowering financing costs and by prompting investors to shift into other assets, raising their prices and stimulating additional spending and investment. In short, conventional policy works mainly via the policy rate, while QE acts across the entire yield curve by increasing liquidity and easing financial conditions.

Quantitative tightening (QT) is the reverse of QE and reduces the central bank’s balance sheet once conditions have strengthened and inflationary pressure has built. QT can either be passive, where the central bank gradually shrinks the balance sheet by allowing securities to roll off as they mature, or active, where bonds are sold before maturity, thereby withdrawing liquidity more quickly and putting more immediate pressure on yields.

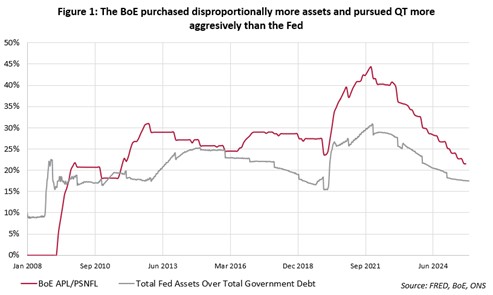

The Bank of England (BoE) claims that, unlike QE, which aimed to affect interest rates and growth, QT is intended to restore policy flexibility rather than act as an additional tightening tool. Even so, QT affects the economy by raising yields and reducing liquidity. The impact depends on the size and method of balance sheet reductions. Empirical work suggests QT has lifted gilt yields by 30-70bps, reflecting the BoE’s larger relative holdings and active sales, versus roughly 20bps at most across the US curve under passive QT.

From 2008 to Today: QE and QT in the US and UK

Both the US and UK turned to QE after 2008 and repeated and enlarged those programmes during the pandemic. They are now several years into reversing those actions through QT, with the US having ended QT very recently on 1st December 2025 and the UK proceeding at a slower pace.

The US moved into QT much earlier than the UK. From 2017, the Fed began shrinking its balance sheet by allowing a capped amount of maturing securities to roll off each month. This reduced reserves and by late 2019 it became clear that market liquidity was reducing. Overnight rates spiked and the effective federal funds rate exceeded the target range, forcing the Fed to halt QT and resume liquidity provision. The pandemic then brought a much larger phase of QE in both economies. This QE underpinned aggressive fiscal support and a rapid rebound in activity, but also contributed to the inflation overshoot once supply constraints and strong demand collided, unlike in 2008 when impaired and deleveraging bank balance sheets prevented such liquidity from circulating.

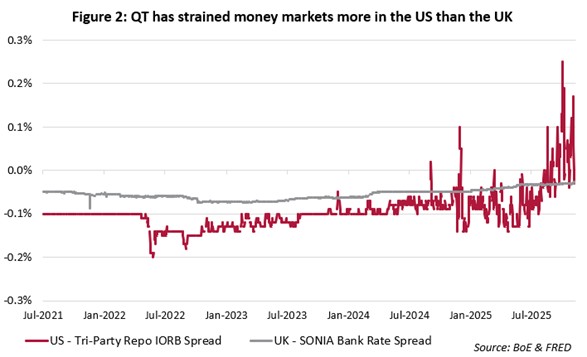

As inflation surged in 2021 and 2022, both central banks tightened policy and began QT. By late 2025, the Fed’s balance sheet had fallen by about $2tn and reserves had dropped sharply. Stress appeared in US money markets as the spread between the federal funds rate and overnight rates widened and the use of repo facilities increased. The Fed judged that QT had reached its practical endpoint and announced that run-off would cease on 1 December 2025. It will now resume T-bill purchases, so the balance sheet grows roughly in line with the economy, maintaining an “ample reserves” regime rather than returning to pre-crisis proportions.

In the UK, the BoE began QT in 2022 and chose a mixed strategy. It stopped reinvesting maturing gilts and undertook active gilt sales to increase the pace of reduction, given the long maturity profile of its holdings of UK government debt. As yields rose and prices of gilts bought during the ultra-low rate period fell, the APF began generating significant losses which fell on the Treasury under indemnity and have cost taxpayers billions. The BoE is likely to continue QT for some years, but has been clear that its pace and composition will be calibrated to market conditions and fiscal considerations. For instance, the QT strategy was altered to both reduce sales and re-weight them away from the long end of the yield curve, which has faced substantial upward pressure in recent months. However, critics argue that the Bank has continued QT when pausing would have been beneficial to the UK economy, fiscal position and markets.

Bank reserves, money markets and the viability of QT

For both central banks, QT can only proceed while they retain adequate control of the overnight rate. Once reserves fall close to the minimum level needed for those frameworks to function smoothly, QT must be slowed or stopped. This is what Figure 2 shows on the US side: as QT progressed, the spread between repo rates and interest on reserves widened, confirming that the system was approaching the lower bound of ample reserves, a sensitivity that reflects the more market-centred, non-bank-driven structure of US dollar funding markets compared with the more bank-centred sterling system. That dynamic was a key reason why the Fed ended QT in 2019 and again in December 2025.

QT in the UK can continue while reserves remain ample. As long as overnight sterling rates stay in a narrow band just below Bank Rate and there is little stress in overnight cash markets, the Bank sees no need to adjust. The right-hand side of Figure 2 shows that although the SONIA–Bank Rate spread has narrowed, it remains stable, in contrast to the more pronounced volatility in US funding markets, suggesting that BoE QT does not yet face the same money-market headwinds as in the US. That said, liquidity pressures from QT are visible elsewhere in the monetary system, with usage of the BoE’s short-term repo facility having risen since the start of QT to a record £97bn level earlier this month. This suggests that the Bank is already relying more on its liquidity tools and will need to calibrate any further balance sheet tightening carefully.

What comes next?

With US QT now ended, the Fed has moved to a regime of reserve management purchases (RMPs) of T-bills. These purchases expand the balance sheet, but they are not QE because they are focused on stabilising money markets, not monetary easing across the curve. Under RMPs, the Fed buys short-dated bills so that aggregate reserves grow broadly in line with the size of the economy rather than drifting down. RMPs are likely to keep T-bill yields lower, all else equal, and modestly support activity, but over time may put upward pressure on inflation by supporting short-term funding and repo activity and making it easier to finance activity.

The BoE still believes it has further to go on QT, as its balance sheet remains very large relative to the UK economy, despite signs that UK banks are drawing ever more cash through its repo facilities. The Bank has signalled that QT will continue with a combination of passive runoff and a manageable volume of active sales, subject to periodic review. While reducing the quantum at a recent MPC meeting, the amount of active sales will actually increase, which will continue to undoubtedly place further upward pressure on yields at a difficult time for the UK’s fiscal position. Given this, we should expect QT to continue to contribute to the elevated term premia on UK government debt over the coming years – good for investors, not so good for borrowers.

12/12/2025

Related Insights

What will Markets be watching in the Budget?