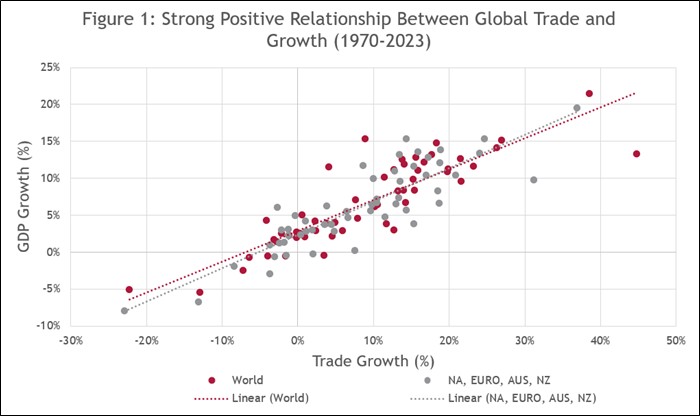

For three decades before the global financial crisis, trade was arguably the world economy’s most powerful engine of growth. From the 1980s until 2007, global trade volumes expanded at roughly twice the pace of global GDP. Research by Frankel and Romer (1999) suggests that trade is not only a byproduct of growth and development but also an active driver of it: their estimates suggest that a 1% increase in the trade-to-GDP ratio boosts per capita income by 0.5% to 2%. In short, trade and GDP rose in tandem, a strong positive relationship clearly visible in Figure 1.

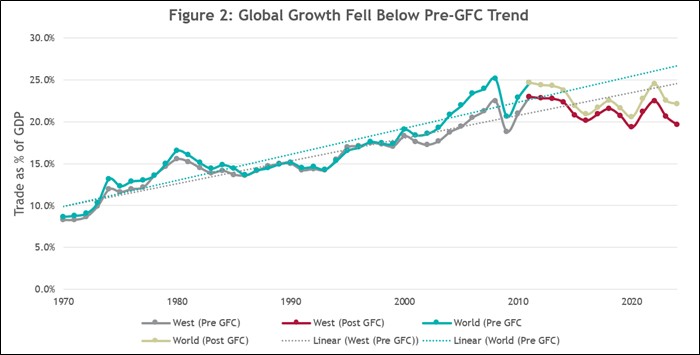

Since the 2008-09 crisis, this relationship has broken down. From the mid-2010s onward, trade as a proportion of output stagnated, never regaining its pre-crisis trend (Figure 2). Why the slowdown?

Much of the contemporary trade weakness is due to persistent structural factors rather than just cyclical weakness in demand. One major structural factor is the maturation of supply chains, as one-off gains from earlier reductions in transport costs, tariffs, and other trade barriers have largely been exhausted. Additionally, China’s extraordinary export surge was a huge driver of global trade growth before 2008. In recent years, however, China has shifted toward a “dual circulation” model emphasising domestic consumption, so its role as an engine of import demand growth for others has diminished. In short, world trade is not growing as it once was - the trade elasticity (trade growth per unit of GDP growth) has declined.

Another structural drag has come from geopolitics and policy. Globalisation has run into headwinds from rising protectionism. Even before Trump’s second term as President and the “liberation day” tariffs, a wave of protectionist measures - tariffs, quotas, and sanctions - raised uncertainty and partly reconfigured trade flows. For example, as noted in a World Bank blog, the number of trade treaties signed each year decreased by more than half since the 2000s, while nearly 3,000 trade restrictions were imposed in the same period. While these restrictions often reallocated trade rather than destroyed it, they nonetheless dampened growth.

The reinstatement of Trump as US President in January 2025 unleashed new tariff shocks. Key measures include 50% tariffs on steel, aluminium, and copper and 25% on imported cars. In addition, an “across-the-board” 10% tariff was declared in April 2025, triggering immediate market volatility before being paused and modified sporadically as part of broader negotiation processes. The effect on effective US tariff rates has been dramatic. The most recent analysis from Yale University’s US Tariff Tracker reports that the average US tariff on all goods jumped from 3.0% to 18.6%, the highest since 1933. Average US tariffs on Chinese imports alone spiked even higher to 127% in early May before retreating to an effective rate of 27.9%. While the US tariff offensive has been disruptive globally, the UK (luckily) managed to secure certain concessions via the new UK-US Economic Prosperity Deal for some exports such as cars, steel, pharmaceuticals, and aerospace components. The effect of this preferential treatment by Washington may prove beneficial for UK growth, as the Yale Budget Lab expects the UK economy to be 0.2% larger, all else equal, due to trade diversification effects wherein US demand shifts from more heavily tariffed countries to the UK.

Nonetheless, the overall impact of these trade frictions is negative for global growth. Major institutions like the Federal Reserve, OECD, and World Bank have each cited tariffs as a factor behind their downward revisions to US and global GDP forecasts. Indeed, by mid-2025, consumer and business sentiment in the US had swung from optimism to pessimism as policy uncertainty surged. In short, trade, once a tailwind, has turned into a headwind for the world economy.

What, then, has been driving GDP growth in the post-crisis period if not trade? Aggressive monetary and fiscal stimulus supported growth even as exports lagged: interest rates were slashed to new lows, central banks undertook massive quantitative easing that propped up asset prices and, by extension, consumer spending, and large fiscal deficits became the norm to sustain aggregate demand.

The question is whether policymakers can continue to rely on domestic levers to drive growth. One option is fiscal stimulus. However, fiscal space in both the UK and the US is now heavily constrained as debt levels are at or near peacetime highs and servicing costs have risen with interest rates. This limits how much more governments can borrow and spend without undermining market confidence or violating fiscal rules. Thus, while targeted public investment (in infrastructure, green energy, etc.) could boost growth, the scope for a big debt-funded fiscal push is largely off the table. Monetary policy, the other traditional lever, is likewise constrained. As inflation still remains a concern, there is little room to cut rates aggressively or use unconventional easing to stimulate growth without exacerbating price pressures. Should a downturn hit, central banks will of course respond, but their capacity to proactively fuel growth is weaker than a decade ago. All of this means that neither of the standard levers - fiscal or monetary - is positioned to drive a robust acceleration in growth for the UK or US in the immediate future.

In the absence of a trade boom or strong policy stimulus, attention shifts to productivity and innovation as the fundamental drivers of long-run growth. Technological progress could provide an alternative engine if breakthroughs translate into higher productivity growth. There are some grounds for optimism here: advances in digitalization, automation, and AI hold the potential to significantly raise output per worker in the coming years. If firms and governments capitalize on these innovations, productivity gains could accelerate, delivering higher growth even without a trade tailwind. Currently, however, attempts to measure a productivity or profitability boost have been disappointing, with recent research showing 95% of firms are getting zero return from AI implementation. Additionally, it must be noted that productivity performance in both the UK and the US has been disappointingly weak for much of the past decade. The UK, in particular, suffers from a well-documented “productivity puzzle,” with productivity (output per hour) barely growing since 2008. Moreover, the payoff from innovations often has a long lag, meaning the gains from AI or other tech might not fully materialize in GDP statistics for years.

Considering all these factors, the short- to medium-term outlook for growth is one of subdued expectations. Trade is expected to remain sluggish or even contract relative to GDP, reflecting both persistent protectionist trends and the broader global trade slowdown. Fiscal policy will offer only cautious support at best, as governments tread a fine line between stimulating growth and debt sustainability; at worst, fiscal consolidation to reduce debt burdens could become a drag on growth. Monetary policy, meanwhile, is oriented toward controlling inflation and cannot be highly expansionary under current conditions. This leaves the baseline forecast as a continuation of the recent trajectory – essentially muddling through with modest growth or potentially stagnating further under the strains of weaker trade, hypothetical fiscal austerity, and other headwinds.

15/09/2025

Related Insights

Is Financial Repression Coming Back?