As public debt levels continue to rise across Western economies with no effective consolidation in sight, financial repression may return as an increasingly prevalent tool for managing debt and mitigating default risk. Although such a policy shift is uncertain and, if implemented, would occur gradually, monitoring its potential emergence may prove valuable for risk management and forecasting.

Financial repression refers to a spectrum of policies that allow governments to reduce borrowing costs and liquidate high public debt by using regulatory and institutional tools to channel domestic savings towards government financing at below-market rates. Such policies aim to lower nominal interest costs and, when combined with moderate inflation, produce negative real rates that erode the value of debt relative to GDP.

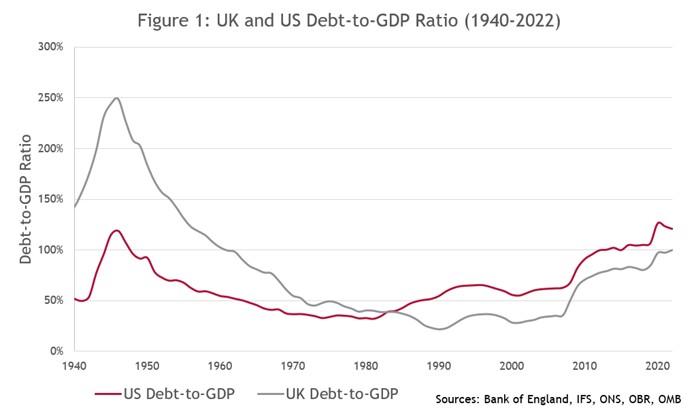

Such policies are not new and were employed as a key tool across advanced economies during the postwar period from the 1940s to the 1970s to reduce the substantial debts accumulated during the war. One notable US policy was an explicit interest rate peg maintained throughout WW2 and the Korean War until the 1951 Fed-Treasury accord. Designed to keep government borrowing costs low, the peg fixed short-term Treasury bill rates at 0.375%, even as inflation surged to 17.6% between 1946 and 1947. This policy pushed real interest rates well below market equilibrium and significantly contributed to real debt liquidation. IMF simulations suggest that, without these artificially low real rates, the US debt-to-GDP ratio in 1974 would have been 51% higher (74% instead of 23% as actually occurred). As seen in Figure 1 below, such policies were effective in liquidating government debt until fiscal expansion began in the late 20th century.

As Reinhart & Sbrancia (2015) note, a range of additional policies contributed to financial repression during this period. Capital account restrictions and exchange controls under Bretton Woods trapped domestic savings within national borders, creating a captive investor base. This was reinforced by high reserve requirements and prudential regulations mandating that institutions hold government securities, while transaction taxes on equities made non-sovereign investments less attractive. Collectively, these measures and others funnelled private capital toward sovereign debt and maintained the low real interest rate environment necessary for debt liquidation.

The UK adopted a broadly similar approach during the period, most notably through the Exchange Control Act of 1947 and the continuation of the “cheap money” policy, which kept the Bank Rate exceptionally low. These measures were reinforced by high liquidity requirements for banks and informal pressures on institutional investors to hold gilts. Like in the US, this combination suppressed real interest rates and channelled domestic savings toward government debt, facilitating postwar debt reduction.

Monetary institutions and policy frameworks have changed considerably since the postwar period, alongside significant trade and financial liberalisation. Yet elements of financial repression persist today and could intensify as concerns surrounding the sustainability of sovereign debt emerge amid political deadlock.

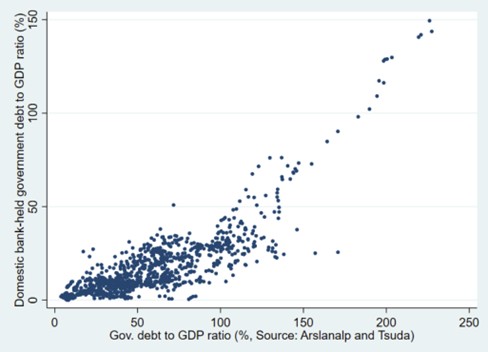

However, not all the policies associated with financial repression must occur simultaneously. Jeanne (2025) defines financial repression as a 3-stage process: in the initial stage, the government can finance itself largely through market mechanisms, placing debt with non-bank investors without any special intervention or distortions. However, once the debt burden grows beyond a critical threshold (empirically estimated around 100-120% of GDP), this dynamic shifts. At this point, the banking sector absorbs most newly issued debt, a pattern clearly illustrated in Figure 2. This phase is referred to as balance-sheet financial repression by Jeanne. One example of balance-sheet financial repression in the UK has been post-GFC regulation mandating banks to hold more High-Quality Liquid Assets (primarily Gilts) under Basel III liquidity rules, thereby increasing statutory demand for government bonds and helping finance the post-crisis debt expansion.

Figure 2: Bank-held government debt vs. total government debt in advanced economies (% of GDP)

Figure source: Jeanne (2025) Data source: Arslanalp and Tsuda (2014)

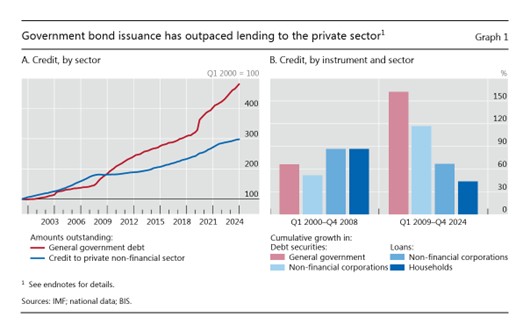

This process necessitates either reducing lending to the real economy (crowding out) or expanding deposits (crowding in). Jeanne suggests that balance-sheet financial repression is associated with crowding in, as the change in bank-held government debt (%GDP) was not associated with a drop in bank lending (%GDP) across the sample. If correct, this means the government is effectively using banks to fund deficits, yet without sharply distorting interest rates or reducing private credit in the short run, meaning distortionary costs are moderate. However, BIS notes that after the GFC, financial intermediation has increasingly shifted from financing private investment towards governments (Figure 3). This suggests that even if crowding in dominates currently, bank behaviour may still result in a gradual crowding out of private credit, especially as sovereign financing becomes more central to bank balance sheets.

Figure 3: Government Debt Is the Main Driver of Credit Growth

Source: BIS Annual Economic Report 2025, (pg. 48)

If debt continues climbing unabated, the process may escalate to a final stage (quasi-fiscal financial repression) in which the government starts extracting quasi-fiscal revenue from banks. At this final stage, authorities impose explicit constraints like below-market interest rates on government bonds or caps on deposit and lending rates. Banks might be required to hold government debt at artificially low yields or accept suppressed interest on reserves, effectively transferring resources to the state. This is highly distortionary and resembles the strict interest rate controls and credit directives seen in the mid-20th century.

Importantly, Jeanne’s empirical evidence suggests that many economies have stayed in the milder balance-sheet phase. For instance, several G7 countries likely entered balance-sheet repression once their debt exceeded about 100% of GDP (figure 3), yet even Japan (with debt over 200% of GDP) has so far avoided resorting to the most distortive, quasi-fiscal measures. This implies that countries like the US and UK may still have considerable leeway to manage high debt through the banking system.

However, risks remain surrounding the implementation of financial repression. For example, calls to remove Jerome Powell and appoint someone committed to aggressive monetary easing while framing rate cuts as a tool for debt sustainability reflect a desire to return to the fiscally dominated monetary policy of the mid-20th century. As President Trump wrote on Truth Social, “Fed should cut Rates by 3 Points. Very Low Inflation. One Trillion Dollars a year would be saved!!!” (July 15, 2025). Some thinkers on the American populist right, in more extreme examples, are seeking to restructure the economic system along nationalist and anti-globalist lines. A prominent example is Stephen Miran, recently nominated to serve as a Federal Reserve Governor and known for his role as Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers and as an architect of the Mar-a-Lago Accords, outlined in his paper A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System. In this paper, Miran proposes several measures that can be characterised as forms of financial repression. Notably, he suggests invoking the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to impose a “user fee” on foreign holders of US Treasuries by withholding a portion of their interest payments and redirecting it to the Treasury. This approach effectively lowers the yield paid to foreign investors below market rates, thereby attempting to reduce government borrowing costs.

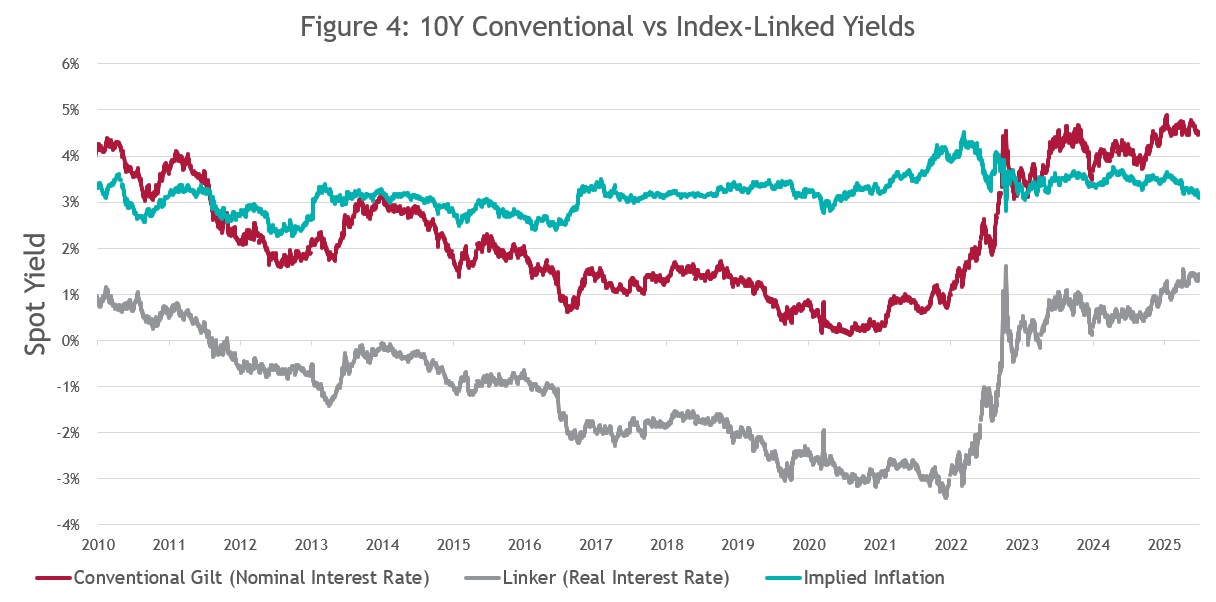

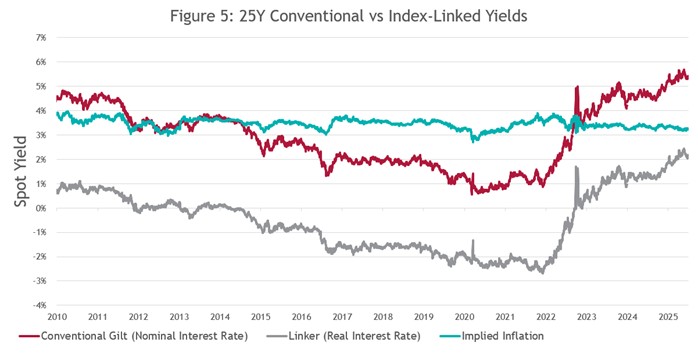

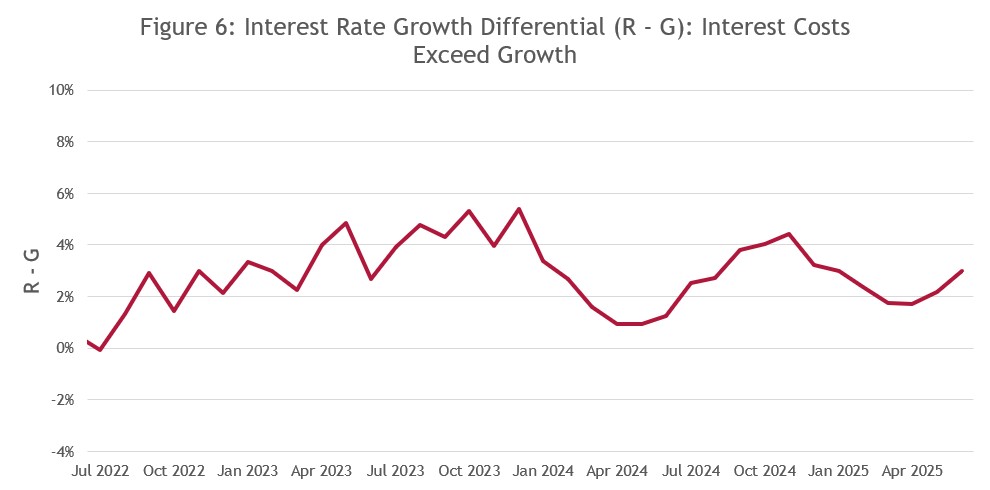

Even on the more moderate side of the Atlantic, there remain strong incentives for the government to reduce real interest rates and fiscal pressure, particularly given HM Treasury’s fiscal rules and its ongoing difficulties in adhering to them. Over the past three years, real interest rates have played a significant role in exacerbating the UK’s fiscal unsustainability. This dynamic is evident in the UK’s interest-rate-growth differential. That is, the difference between the real interest rate (R) and the real economic growth rate (G). When the economy grows faster than the interest burden on debt (G > R), the government can stabilise or reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio without running a budget surplus, as economic growth outpaces the accumulation of interest obligations in real terms. Conversely, when R > G, the debt-to-GDP ratio rises unless the government runs fiscal surpluses, as interest costs compound more rapidly than the economy’s capacity to generate real output and revenue.

As shown below, the sustained rise in real interest rates since 2022, following more than a decade of negative real rates, is placing growing pressure on the government’s fiscal position, particularly at the longer end of the yield curve. In this context of a worsening budgetary outlook and political gridlock hindering fiscal consolidation, the incentives to pursue financial repression are becoming increasingly pronounced.

Indeed, several proposals reflect a growing inclination toward financial repression. For example, both the New Economics Foundation, a socialist think tank, and the right-wing Reform UK party have advocated ending interest payments to banks on reserves held at the BoE, a move projected to save the Treasury £30-40 bn. While the debate over the remuneration of reserves is legitimate, such a policy would function as a de facto quasi-fiscal tax on banks and exemplify both financial repression and fiscal dominance over monetary policy. Similarly, calls for the BoE to slow or suspend its QT program, intended to keep interest rates lower and reduce government borrowing costs, would also fall under this category, despite being open to reasonable debate. Finally, proposals such as those put forward by financial lobbying group UK Finance to “remove cliff edges in capital and leverage requirements which create constraints on balance sheet expansion… to help boost … gilt market liquidity” closely resembled the balance sheet-based financial repression seen in post-war Britain. Such measures would effectively transfer value from savers to the treasury by suppressing interest rates and directing capital towards sovereign financing.

Given these developments, financial repression should not be treated as a historical anomaly but as an active policy variable of growing relevance. While the implementation of the measures outlined above, or similar ones, is neither guaranteed nor necessarily likely, forward-looking analyses should incorporate repression risk when projecting interest rates, inflation, and financial sector profitability. Monetary, fiscal, and regulatory decisions are increasingly likely to be influenced not only by inflation, employment, and growth considerations, but also by the imperative to manage debt-servicing costs. Accordingly, attention to incremental or indirect shifts towards repression, whether through changes in capital requirements, reserve remuneration, or the pace of quantitative tightening, is essential for understanding the evolving macro-financial environment.

If you would like more information on our economic forecasting and analysis, please contact us at treasury@arlingclose.com or 08448 808 200.

Related Insights

Have we really entered a post-pandemic era of higher policy rates?

Medium Term Note Programmes: A Flexible Tool for Borrowing at Scale