Police and fire authorities are often spoken about in the same breath as local councils, but in truth they are structurally different public bodies. For anyone involved in finance, governance, or treasury management, assuming they behave like smaller versions of local authorities is not wholly accurate. Their funding models, governance frameworks, and risk profiles are distinct, and those differences are becoming even more significant as devolution accelerates across England. Police and fire are functions of the devolved governments in Northern Ireland and Scotland.

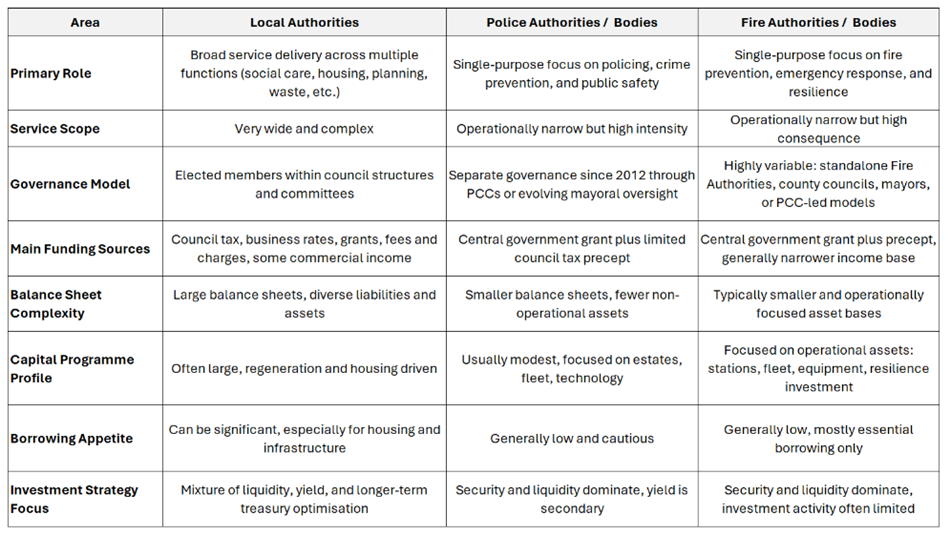

A principal local authority exists to deliver a broad range of services, from adult social care and housing through to planning, waste, education, and economic development. That breadth creates complex financial structures, larger balance sheets, and wide-ranging revenue sources. Police and fire authorities, by contrast, are operationally narrow but strategically intense. Their core functions are straightforward: frontline emergency response, public safety, and resilience. They exist to deliver critical services under constant scrutiny, with little margin for financial disruption.

Governance is where the distinction becomes even sharper. Councils operate through elected members within relatively stable democratic structures. Police governance, however, has sat separately since 2012 through police and crime commissioners (PCCs), and the direction of travel under the Government’s devolution agenda increasingly points towards greater integration into mayoral and combined authority oversight.

Fire governance is even more varied. Some fire and rescue services are overseen by standalone fire authorities, others sit within county council or unitary authority structures, and several have already transferred responsibilities to elected mayors. In some areas, PCCs have also assumed fire governance functions, creating police, fire and crime commissioner models.

The result is a fragmented and evolving accountability landscape, with significant implications for financial decision-making, scrutiny, and treasury governance as reforms continue.

In November 2025, the UK Government announced that PCCs in England and Wales will be abolished by 2028, describing them as an expensive and ineffective layer of accountability and signalling a move towards alternative oversight arrangements instead. This is not a minor tweak; it is the biggest structural shift in police governance since 2012.

Ministers argued that PCCs have failed to improve policing accountability in proportion to their cost, highlighting that the system supports 41 separate commissioner offices across England and Wales, each with its own staffing and administrative overheads. The Government pointed to the combined cost of PCC structures running into tens of millions of pounds each year, alongside concerns that public engagement remains weak, with PCC election turnout typically around 20-30%.

Police and fire authorities have far less financial flexibility than councils. Principal local authorities can draw on wider income streams, including business rates, fees, and in some cases commercial activity. Police and fire bodies rely heavily on government grant and a limited council tax precept. That makes them more exposed to central spending decisions and less able to manage pressures independently. Operational demand rises regardless of funding settlements, and that creates persistent structural strain.

From a treasury management perspective, police and fire authorities tend to be more liquidity-driven and risk-averse. They usually hold smaller cash balances, have less complex capital programmes, and do not have the same borrowing appetite seen in housing or regeneration-heavy councils. Their overriding priority is maintaining operational continuity, not treasury optimisation. In practice, investment strategy is typically about security and liquidity, not yield.

Summary: Local Authorities vs Police and Fire Authorities

Looking forward, the devolution reforms underway are going to make the landscape messier before it becomes clearer. Transferring policing powers into mayoral offices may improve strategic alignment with wider public service delivery, but it also concentrates accountability in fewer hands and risks weakening local scrutiny if governance arrangements are not robust.

Further integration through devolution may improve coordination on resilience and emergency planning, but it could also create inconsistent accountability models and reduce visibility of fire oversight in systems dominated by larger political priorities.

The key question for both services is whether the next governance framework strengthens operational accountability or simply rearranges it.

If you would like support reviewing your treasury approach, please contact us at treasury@arlingclose.com.

06/02/2026

Related Insights

How to measure local authority creditworthiness?

Are Treasury Teams Ready for Local Government Reorganisation?

How Does Adjustment-A Impact Local Government Reorganisation?