At Davos, Mark Carney, the current Prime Minister of Canada and former Governor of the Bank of England, joined other commentators in declaring the end of the US-led rules-based international order. Carney contends that the old order is being replaced by one defined by “intensifying great power rivalry, where the most powerful pursue their interests, using economic integration as coercion”, and implores middle powers to develop strategic autonomy by recalibrating their relationships so that they are broader and calibrated to the degree of shared values. While the US has always been an imperfect enforcer and representative of the rules-based order, it is not difficult to see why the events of the second Trump administration – such as attacks on the sovereignty of NATO allies, increasing weaponisation of the US’s economic tools, unilateral action on Venezuela, growing normative dissonance with allies, and increased brinkmanship with China – constitute a more fundamental shift in the international order in the eyes of leaders around the world. However, many questions remain. Is it right to characterise recent events as a sea change, given that US actions would be markedly different under different leadership? What would a more coercive, realist, and less integrated global economic and financial system look like in terms of currency reserve management, trade, investment flows, financial infrastructure, and sovereign debt markets?

While the second Trump administration is the most transgressive in recent memory, it is not the first to depart from international norms. It remains possible that a future administration, like Biden after Trump’s first term or Obama after Bush, may attempt to repair the relationships with the US’s international partners. However, it is increasingly implausible that such efforts would restore the former system in full. The imperative to cultivate sovereignty, as outlined in Carney’s speech, is likely to become structurally embedded in Western strategic thinking. The US’s allies, unwilling to see their economic and geopolitical circumstances at risk every four years, are likely to view some degree of insulation from the US’s political volatility as important to national security. Therefore, this shift is unlikely to reverse and will continue to influence the global financial system in the years ahead. While forecasting the trajectory of international change, let alone the long-term effects of such changes on markets, is difficult, empirical evidence already illustrates the possibilities. A more coercive and less predictable order will alter how risk, capital, and institutional trust are allocated, and those countries pursuing greater autonomy will likely face high costs.

The inverse relationship between geopolitical fragmentation and economic integration is well documented. Between 2017 and 2024, estimated trade between geopolitical rivals was 4% lower than it would have been in the absence of increased geopolitical tensions. Although total global trade volumes have been sustained, bolstered in part by non-aligned states expanding their intermediary role, this compensatory effect may not continue in the future. If America’s posture continues to lean towards transactionalism and economic coercion, a broader reduction in its trade with the rest of the world would likely follow. However, as the US only comprises around 13% of global imports, total trade could be sustained through alternative trading partners, particularly where non-aligned countries continue to expand trade.

Cross-border investment has shown a similar pattern of retreat. As geopolitical distance grows, foreign direct investment, cross-border lending, and correspondent banking relationships have diminished, all else equal, producing headwinds against the financial efficiencies they enable. While aggregate investment has been preserved within politically aligned blocs, this insularity increases exposure to regional shocks and weakened alliances. In short, as geopolitical fragmentation increases, the global economy will be less dynamic and flexible. This retreat also has implications beyond capital allocation. Global financial stability has long relied on the availability of dollar liquidity in moments of stress, with the Federal Reserve acting as an international lender of last resort through swap lines and emergency funding facilities. In a more fragmented order, access to such liquidity may become increasingly contingent on political alignment rather than purely systemic need.

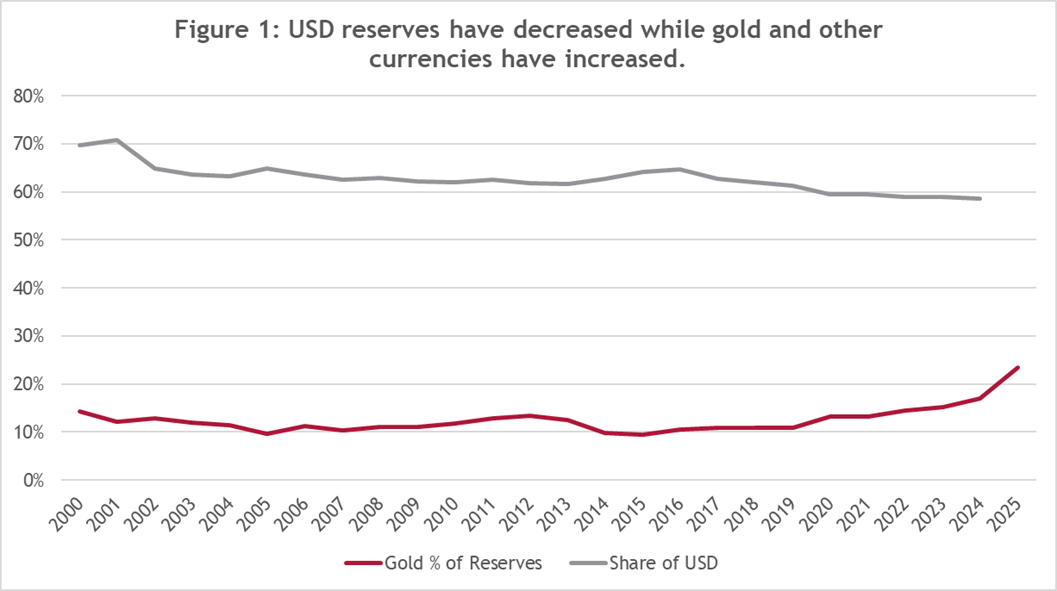

One of the clearest long-term implications of geopolitical fragmentation is a gradual realignment of currencies and capital flows in response to geopolitical uncertainty. For decades, the US dollar has been central to the international monetary system, accounting for 60% of foreign exchange reserves and 90% of FX transaction volume. America’s willingness to use its position in the global financial system to leverage sanctions against both adversaries and allies to extract political or economic gains has prompted many countries to rethink their dependence on the dollar. Against this backdrop, countries like China, India, and Brazil have started conducting more trade in their own currencies, cutting out the dollar as an intermediary. As Figure 1 shows, the ‘de-dollarisation’ trend has been gradual but it points toward a more multipolar currency order over the long run. If US governance continues to be seen as erratic or self-interested, global investors may increasingly hedge against this by allocating capital to a wider mix of assets and currencies. Sovereign bond markets would feel these shifts: for instance, reduced appetite for US Treasuries by foreign central banks and investors could raise borrowing costs, while countries seen as stable and values-aligned (like the UK) might attract more safe-haven flows. At the same time, the pursuit of strategic autonomy is unlikely to be costless. Greater emphasis on defence, industrial policy, and domestic resilience across Europe and other middle powers implies structurally higher public spending and, in many cases, increased sovereign issuance. Over time, this may place upward pressure on borrowing costs and term premia, even for fiscally credible states. Furthermore, greater uncertainty could raise term premia across all countries, and countries outside the US could face higher financing premiums if access to America’s deep capital markets comes with risks. While de-dollarisation is often exaggerated or sensationalised, increased fragmentation and uncertainty would likely disrupt financial markets.

Ultimately, the long-term market impact of this fractured order will be a world of higher transaction frictions and risk premiums. If the US-led rules-based framework gives way to a more divided and volatile landscape, global finance is likely to become less efficient and more prone to instability, with countries and companies paying a price for the “insurance” of economic independence. Yet, as leaders like Mark Carney argue, middle-power nations may judge that the costs are worthwhile if it buys them greater sovereign resilience in an era when economic integration can be used as a tool of coercion. While predicting the path of international relations and the subsequent financial impact is inherently fraught, the exercise remains relevant to investors, as geopolitical structure increasingly shapes risk, capital markets, and the reliability of financial relationships on which long-term returns depend.

Arlingclose advises its clients’ corporate finance and treasury operations through global economic and market volatility. For more information please get in touch with nkeeling@arlingclose.com.

04/02/2026

Related Insights

How Divided is the Monetary Policy Committee?