Assessing creditworthiness is a cornerstone of prudent financial and treasury management. In evaluating the likelihood that a borrower will meet its debt obligations, market participants rely on a range of tools, with credit ratings and credit default swaps (CDS) among the most commonly used. Each offers a different perspective - one more fundamental, the other market-driven - yet both serve as important gauges of credit risk.

Credit ratings are assessments on an entity’s credit risk, typically issued by independent credit rating agencies such as Moody’s, Fitch and Standard & Poor’s (S&P). These ratings reflect the agencies’ assessment of a borrower’s ability and willingness to meet its financial commitments in full and on time, as well as the likely direction of the entity over the medium term (the outlook).

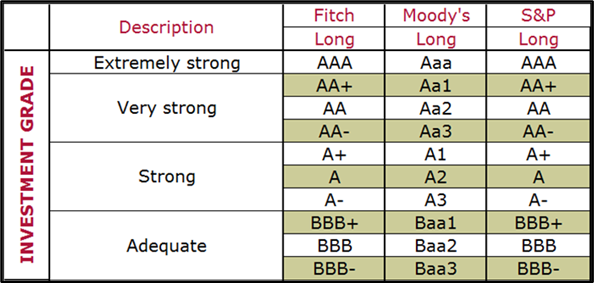

Long-term credit ratings, which are the primary focus in institutional investment decisions, are denoted by alphanumeric codes (e.g. AAA, BBB, Baa1). These ratings are generally categorised into two broad tiers: investment grade and non-investment grade, also referred to as speculative grade or high yield. The distinction between these categories is crucial, as it directly influences investment policy decisions, regulatory requirements, and borrowing costs.

Investment grade ratings indicate a relatively low risk of default and are typically required for institutional portfolios that prioritise capital preservation. These ratings range from the highest quality to adequate credit quality:

For example, a sovereign or corporate bond rated ‘AA’ by S&P or ‘Aa2’ by Moody’s is considered high quality, with a very low likelihood of default. A ‘BBB-’ (or Baa3) rating still qualifies as investment grade but represents the lowest rung of that.

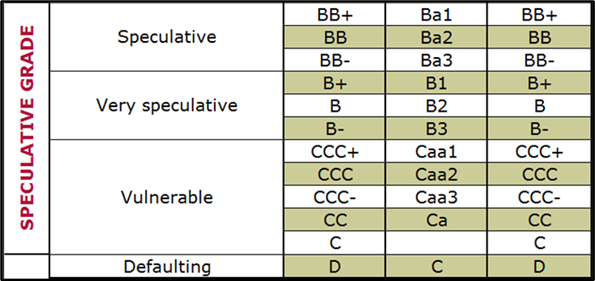

Non-investment grade, or speculative, ratings suggest a higher risk of default, with the potential for greater returns compensating for the elevated risk:

For instance, a bond rated BB+ (S&P or Fitch) or Ba1 (Moody’s) is considered speculative. While such bonds may offer attractive yields, they are more sensitive to economic downturns and shifts in market sentiment. A ‘CCC’ or ‘Caa2’ rating and below often denotes serious credit concerns, and ‘D’ reflects actual default. While the precise definitions differ slightly across agencies, they all aim to provide a relative ranking of credit risk.

The value of credit ratings lies in their simplicity, comparability, and widespread acceptance. They assist investors and counterparties in making informed decisions, allow for regulatory compliance, and can influence borrowing costs. However, they are not infallible and may lag sudden changes in credit conditions.

Credit default swaps, on the other hand, are financial derivatives that provide insurance against the default of a particular issuer. The CDS spread - the cost of this protection - serves as a real-time, market-based indicator of credit risk. A widening spread typically signals increasing concern about creditworthiness, while a narrowing spread suggests improving perceptions.

The CDS market incorporates information from a range of sources, including news flow, economic data, and investor sentiment. This makes CDS spreads a useful complement to credit ratings, particularly in capturing shifts in risk perception ahead of formal rating actions.

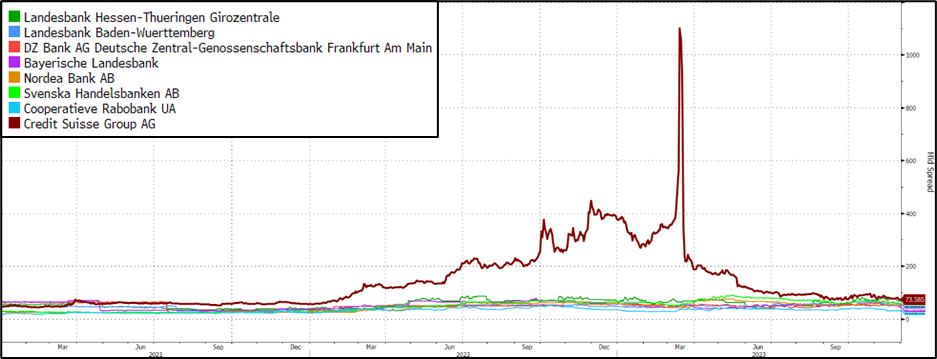

The lag in credit rating changes compared to credit default swaps is clearly illustrated by Credit Suisse. From 2021, the bank’s CDS spreads began to climb after a series of scandals, while its credit ratings remained anchored in investment grade. In March 2021, Credit Suisse lost around $5.5 billion in the collapse of Archegos Capital, having failed to cut exposures as swiftly as peers, yet rating agencies left its ratings unchanged. Throughout 2022, macroeconomic shocks a profitability pressures pushed CDS spreads sharply higher - rising from 55 at the start of the year to 448 by late November - while ratings slipped only gradually to the lower end of investment grade. By 2023, CDS spreads spiked further to 1,100, offering a real-time signal of deteriorating credit quality, compared to peers trading below 100, finally forcing downgrades. CDS markets thus provided a real-time warning of Credit Suisse’s deteriorating creditworthiness, while ratings lagged significantly and never fell below investment grade.

Both credit ratings and CDS spreads are grounded in fundamental credit analysis, however, their methodologies and time horizons differ – credit ratings are more static and long-term in nature, while CDS spreads can reflect near-term volatility and speculation. Used together, these tools, alongside many other credit indicators, provide a more complete view of credit risk. For treasury managers and institutional investors, monitoring both credit ratings and CDS spreads can enhance risk management, inform counterparty decisions, and support portfolio diversification. Understanding the scope, limitations, and complementary nature of each tool is key to navigating today’s complex credit landscape.

To discuss how Arlingclose can support your counterparty risk assessments with clear, evidence-based advice, please contact info@arlingclose.com.

07/10/2025

Related Insights