Financial pressures on universities continue to grow as the combined weight of rising borrowing costs, lower overseas tuition income, and erosion of domestic student fees threatens to push some institutions toward collapse. In the coming years, the challenge will be for universities to make significant savings whilst continuing to deliver services and meet tight borrowing covenants.

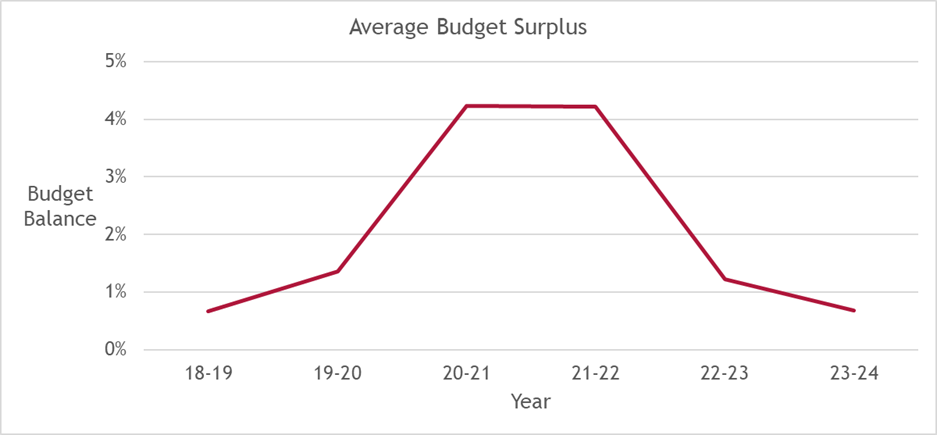

Key indicators point to a general weakening across the sector, as seen in the level of budget surpluses and liquidity. Although budget surpluses were on a rising trajectory from 2018 to 2021, increasing over the period to an average of over 4%, this budget headroom has been almost completely reversed with the current level just marginally above the 2018 level.

Key income from increasing student numbers, especially overseas student numbers, and government support during the COVID pandemic has now waned as the sector reports its third consecutive year of decline. The Office for Students (OfS) reported that as many as 45% of higher education providers are forecasting a reported deficit for 2024/25, a huge increase from the 27% reported the previous year. Although some institutions are forecasting some recovery in the tail end of their five-year forecasts, there are considerable hurdles to jump over to overcome mounting cost pressures, especially as liquidity has begun to show signs of drying up in the sector.

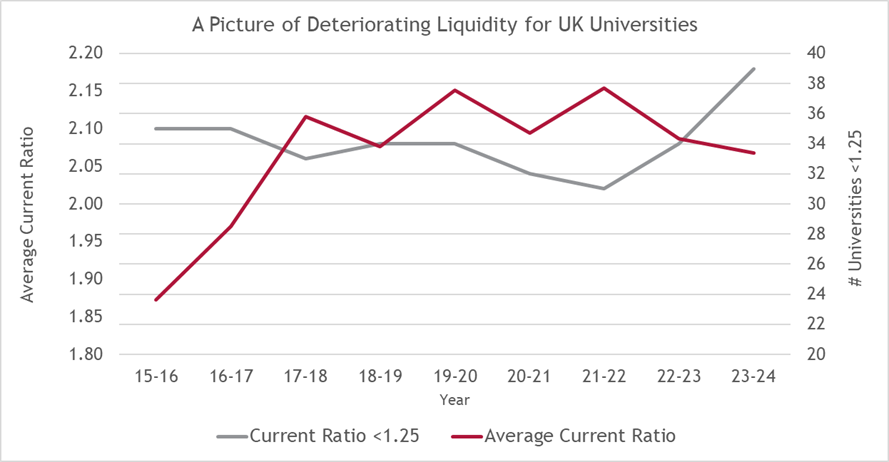

Aggregate cash holdings have fallen 9.8% between 2022 and 2024, while average sector liquidity days fell from 148 days to 126 days, reflecting the falling cash levels available to meet outgoings at universities. Average current ratios have also been declining from their pandemic peaks, accompanied by a sharp pickup in the number of universities with a current ratio of less than 1.25. Rising costs as a result of higher inflation means that crucial capital expenditure projects are taking up larger and larger proportions of budgets. At the same time, higher interest rates mean that borrowing costs are at decade highs, pushing education providers to run down cash reserves in lieu of taking additional costly borrowing.

Long-term borrowing has declined as a percentage of total income over the past four years, as rising costs have increased financial pressure on universities and weakened sector credit quality, making banks more reluctant to lend for significant terms.

Instead, the sector has looked to bolster their short-term balances through increasing usage of Revolving Credit Facilities (RCFs) which allow for additional liquidity if drawn, at the cost of an ongoing non-utilisation fee on undrawn balances. Although these facilities provide vital access to liquidity without locking the borrower in to expensive long-term rates, they are not suitable for ongoing financing requirements and increase the level of interest rate risk in the portfolio as they are subject to a margin over variable short-term rates.

Lenders are increasingly looking to understand the levers that universities have to improve operating surpluses before agreeing to term loans, asking questions around the levels of cost savings, capital expenditure reductions, and staff redundancy schemes to ensure borrowers are able to keep budgets under control. As these schemes take time to deliver meaningful savings, banks are paying increasing attention to other potential cost saving measures that can be drawn on if university forecasts end up being in a downside scenario.

Pressures have been building on universities in recent years due to a combination of rising budget pressures at the same time as a reliance on international student fees has grown. Despite an increase in student fees for UK undergraduates in 2024, these prices have already been heavily eroded by inflation as a result of being capped for eight years. This fall in the real level of fees has led to universities being increasingly reliant on additional income from international students who are not subject to the same cap. The recent OfS report suggests that international student income is expected to account for 60% of forecast tuition growth in 2027-28, a figure which is complicated by the potential impact of geopolitics, exchange rate fluctuations, government policy, and continuing visa restrictions.

Due to patchy student recruitment numbers in 2023-24, which were nearly 11% below forecast, the OfS has deemed some of the university’s forecasts for recovery as “overly ambitious” and suggested they may not fully incorporate upcoming risks. For example, capital expenditure projects have been widely paused due to the increasing cost of both projects and borrowing; these will eventually have to be resumed, as an ongoing underinvestment in capital and infrastructure creates the risk of long-term weakness in the sector. Additionally, if student recruitment numbers are below expectations – a very real possibility given current visa restrictions and the geopolitical situation – this would further strain already fragile budgets and could lead to many universities’ finances coming in well below expectations.

Tightening liquidity, narrowing budget surpluses, and expensive costs of borrowing mean that effective treasury management is of key importance to universities to ensure risk is managed effectively and investment decisions are aligned with underlying cash requirements and long-term capital ambitions. Arlingclose is happy to offer our expertise from advice on setting prudent strategy, through investment and debt advisory services, to negotiation with lenders on covenants.

If you would like more information, please visit our website for more on University Treasury Services, or contact us at nkeeling@arlingclose.com or 08448 808 200.

16/10/2025

Related Insights