Since the global financial crisis, the UK, like many advanced economies, has faced a “productivity puzzle” of persistently weak productivity growth. At a high level, productivity is the efficiency with which the economy transforms inputs into outputs. In practice, it is commonly measured as gross value added (GVA) per hour worked. GVA is the value of output produced minus the value of intermediate inputs, and when aggregated across industries it corresponds to GDP before product taxes and subsidies.

Under growth accounting, changes in GVA per hour can be attributed to three elements: capital deepening, referring to the amount of capital available per worker; labour composition, reflecting shifts in workforce skills and experience; and multi-factor productivity, or MFP, which measures how effectively inputs are combined, including technology and organisation. Sustained gains in productivity are the principal driver of long-run growth and improved living standards. They raise profits directly and wages indirectly, and by increasing value added per hour, they broaden the tax base without higher tax rates. For these reasons, the UK’s productivity slowdown is widely cited as a key cause of lacklustre economic performance, is of critical importance for the Treasury’s budget plans and forecasts, and it is therefore watched closely by bond investors and markets.

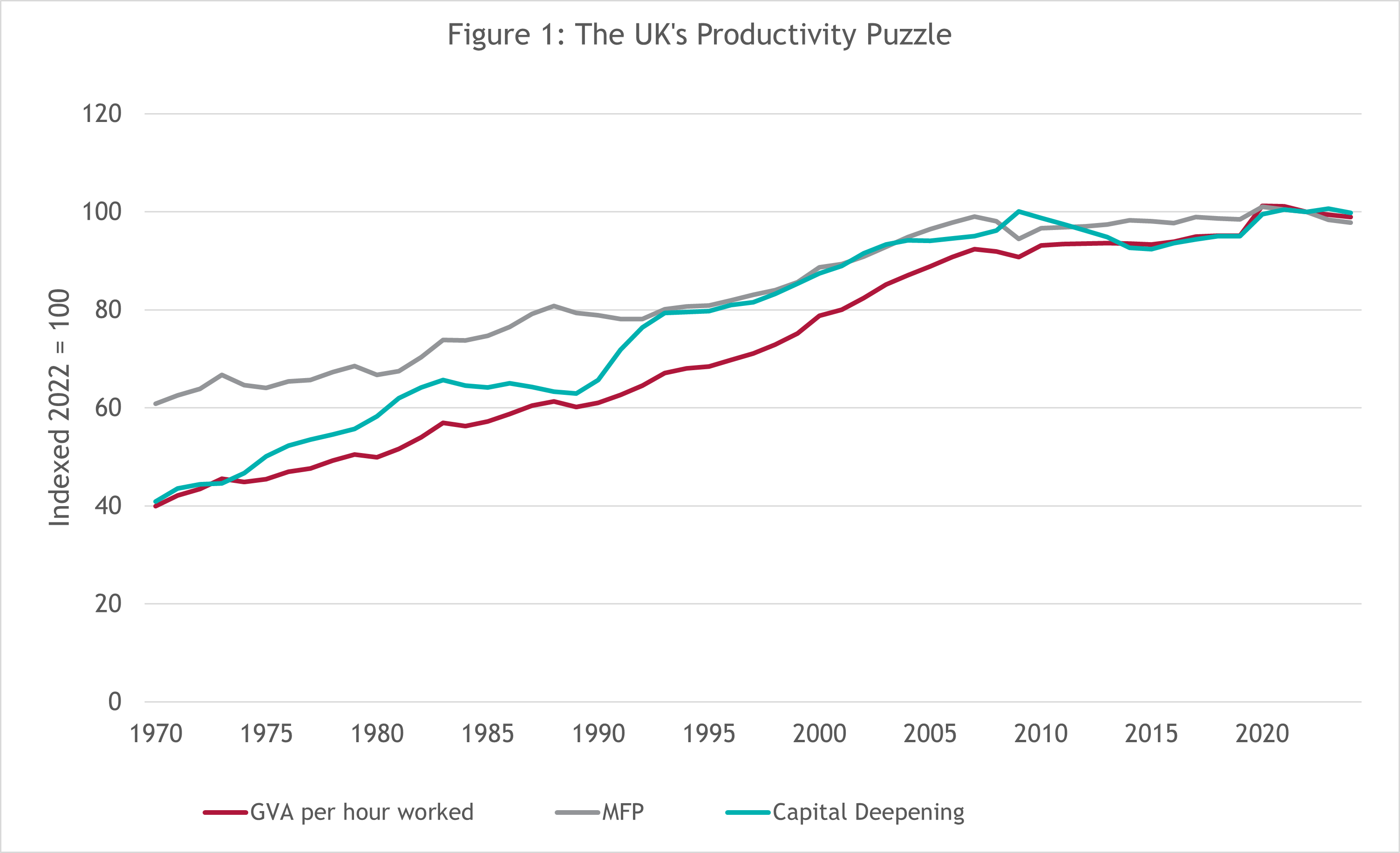

As Figure 1 shows, UK productivity has stagnated since 2008, rising by only 0.45% per year on average during 2011-2024, compared with 2.3% per year during 1970-2006, and it has fallen by 0.5% since 2022.

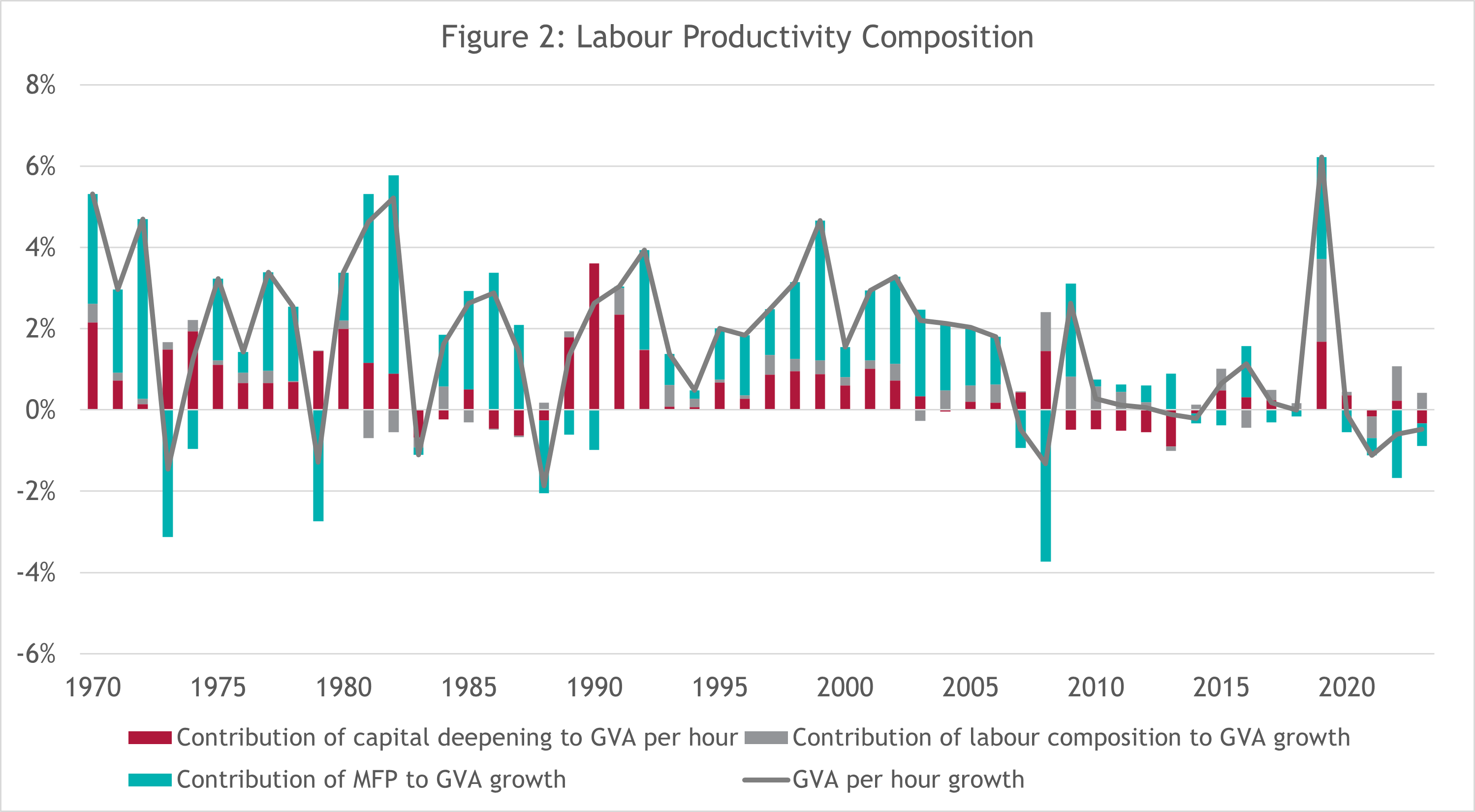

Why has this occurred? A useful starting point is to decompose productivity growth and look at its constituents: capital deepening, labour composition, and MFP. As Figure 2 shows, the post-2011 slowdown reflects both relative capital shallowing, less capital per hour worked, and a deterioration in MFP, partly offset by stronger labour-composition gains. From estimates, about two-thirds of the drop in productivity since 2011 is due to weaker MFP, roughly 45% is due to capital shallowing, and the labour-composition contribution offsets the slowdown by around 8%.

Over the past 30 years, the UK has recorded the lowest investment among G7 countries in 24 of those years. This capital shallowing has reduced productivity, as each hour of labour is supported by fewer or lower-quality capital services, thereby diminishing the marginal product of labour. The decline in MFP aligns with evidence of slower diffusion of technology and knowledge from frontier to laggard firms, underinvestment in intangible assets and organisational capability, and Brexit-related uncertainty and trade frictions, which reduced investment by roughly 11% and directly lowered within-firm productivity by 2-5%.

Recognising the scale of the problem, the Labour government has made boosting productivity a central economic priority. Its approach centres on increasing investment in technology, artificial intelligence, and infrastructure, alongside efforts to improve skills and regional innovation. Whether these initiatives will materially raise productivity remains uncertain, but they mark a shift toward a more interventionist strategy to address the UK’s long-standing investment and productivity gaps.

Whatever the reason for the productivity slowdown, it remains of vital importance to the economy and policymakers – particularly for the Treasury as it plans the upcoming budget in November because the forecasted productivity growth influences GDP growth, employment, corporate profits, wages, and ultimately taxes. Under the UK’s fiscal rules, the government must ensure that public debt as a share of GDP is falling and that public sector borrowing does not exceed 3 percent of GDP within a five-year forecast horizon. These rules determine the government’s “fiscal headroom,” which is the difference between current fiscal policy and the limits permitted under the rules. Because the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) publishes its forecast at the same time as the Budget, the Treasury’s spending and tax decisions must align with the OBR’s latest economic and productivity projections. If the OBR revises productivity growth downward, the resulting reduction in GDP and tax receipts reduces fiscal headroom, likely inducing the Treasury to raise taxes, cut spending, or delay investment plans more than otherwise necessary to remain within the fiscal constraints, lest they get punished by the market.

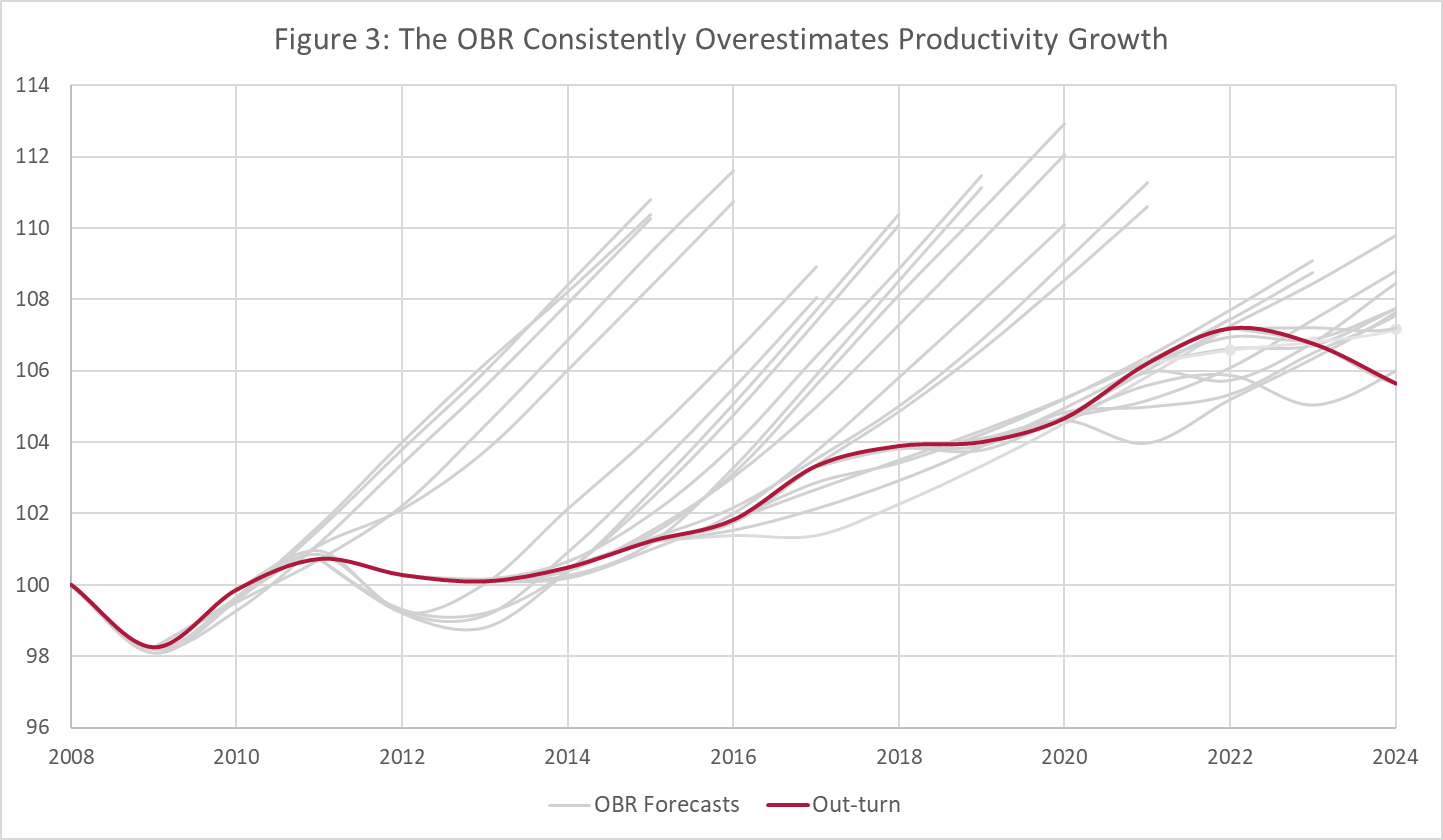

Despite being one of the most important statistics for the Government, the Treasury, and financial markets, the OBR notes that forecasting productivity accurately is a difficult and imprecise task. In fact, as Figure 3 shows, the OBR has consistently overestimated productivity growth in most forecasts since the Global Financial Crisis. This has not only undermined the agency’s credibility but has also led the Treasury to overestimate future receipts and underestimate debt issuance, contributing to the growth of public debt.

In light of these challenges in accurate forecasting, the OBR is currently determining how to approach its upcoming forecast ahead of the November Budget. This decision is complicated by the fact that the forecast is not independent of broader economic outcomes but can itself influence future productivity growth. The IPPR estimates that a 0.1% or 0.3% downgrade in the OBR’s forecast would increase borrowing by £8.7 billion and £26.2 billion, respectively, by 2029-30. In this way, if the OBR were to lower its forecast and prompt the Treasury to raise taxes to cover the projected increased in borrowing, it could inadvertently contribute to the very reduction in productivity it anticipated, even as productivity may have been beginning to recover. Consequently, the OBR must strike a careful balance between providing the government with accurate information to guide policy and avoiding forecasts that induce unnecessarily drastic policy measures.

While productivity might appear to be just another economic statistic at first glance, its growing importance in explaining the UK’s relative economic underperformance in recent years, combined with its influence on the Treasury’s budgetary decisions, has made it perhaps the most influential statistical release of the year. It affects the state of public finances, the political prospects of the Starmer government, and your institution’s borrowing costs, depending on whether markets perceive the Budget and OBR forecasts as credible and conducive to fiscal consolidation.

24/10/2025

Related Insights

What to Expect in the Autumn Budget?