The UK Municipal Bonds Agency (UKMBA) launched with high ambitions: to give local authorities a collective route to cheaper, more flexible capital markets borrowing. Earlier this year it told shareholders that, in the absence of demand for new loans, it would move to “reduced trading” and close to new business, though it will continue servicing existing bonds and loans.

Why did demand fail to materialise, and can the Agency claim credit for lower PWLB margins?

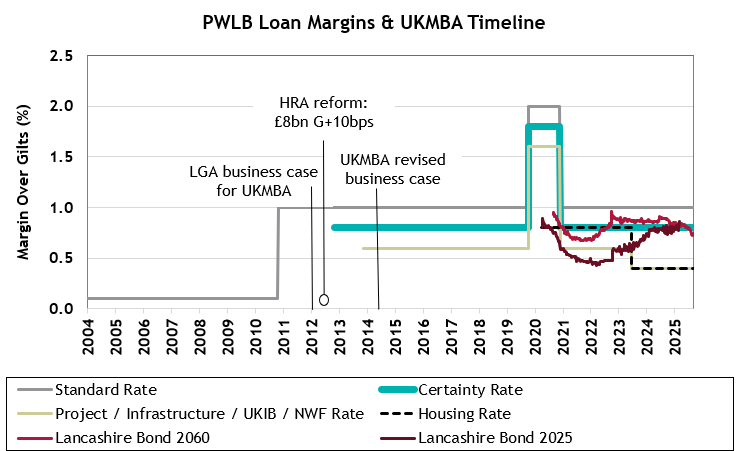

On its core mission of delivering cheaper funding, the UKMBA struggled to compete with the Public Works Loan Board (PWLB). The PWLB’s ease of access, product range, and entrenched role in local government finance ensured its continued dominance. The UKMBA aimed to undercut PWLB pricing, but margins were already slim. Government interventions, lowering PWLB margins, and introducing concessionary rates such as the Certainty, Infrastructure and Housing Rates, further reduced any potential cost advantage. The National Wealth Fund (formerly UK Infrastructure Bank) now lends at gilts +40bps, though demand is limited by project criteria.

The Agency’s only bond issues came in 2020, when PWLB margins had spiked to 180bps. Both for Lancashire County Council, they comprised a £350m 5-year Floating Rate Note (FRN) at SONIA +80bps and a £250m 40-year fixed bond at gilts +100bps. These saved millions versus PWLB rates at the time, but with HMT signalling a margin cut, many authorities deferred borrowing. Although secondary spreads tightened, especially on the FRN, wider sector uptake never followed, and no further bonds have been issued.

A key challenge was the sector’s reluctance to guarantee each other’s debt, whether on a joint and several or proportionate basis. While such guarantees could have lowered pricing by boosting investor confidence, they introduced credit risks that councils were understandably unwilling to accept.

Scale was another hurdle, while Lancashire had the capacity to issue single name bonds in marketable size, other authorities were reluctant to follow and shied away from the requirement to obtain an external credit rating.

The Agency also promoted softer benefits including market oversight, peer accountability, and shared expertise, but these were seen as too intangible to justify added complexity. Ironically, many of these features have since been adopted by government, with HMT introducing stricter oversight and loan vetting following revisions to the prudential code and a crackdown on commercial lending.

Alternatives to PWLB lending have developed, but from elsewhere. Inter-authority loans remain effective for cashflow; shorter-dated commercial loans linked to SONIA add flexibility; and forward-start loans or swaps allow hedging, though they require sophistication. These innovations were not driven by the UKMBA, whose focus remained bonds.

The PWLB retains its appeal through simplicity and adaptability. It has been critical during HRA reform and debt transfers under local government reorganisation, areas where market debt can be cumbersome.

So, did the UKMBA make a difference? Some argue it spent years and millions chasing an alternative to an already effective product. Yet its contribution should not be dismissed. The bonds issued saved Lancashire substantial sums, provided benchmarks for the sector, and offer premature redemption opportunities at much better value than PWLB debt. More broadly, the Agency applied pressure that may well have helped prompt lower PWLB margins and a more competitive environment.

That said, HM Treasury remains more comfortable as the sector’s primary lender. For most authorities, PWLB loans continue to be accessible, flexible, and reasonably priced, and therefore hard to compete against.

01/09/2025

Related Insights