Sitting at home in the UK, watching the economic and market newsflow, past the country’s last peak of coronavirus cases, its sometimes easy to forget the fearful uncertainty of only a few months ago. Now used to working from and spending more time at home and in the immediate locality, it feels like the issue is less immediate and we can look forward to the sunny climes of economic recovery.

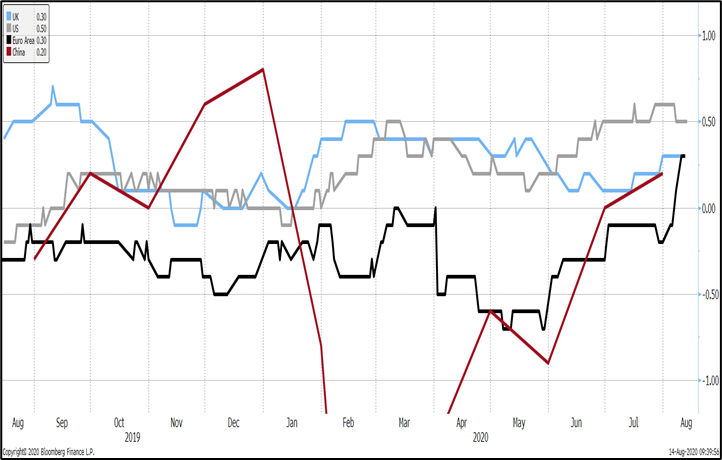

This would generally encourage a more optimistic outlook, but a quick look at the news indicates regional lockdowns, outbreaks at M&S suppliers and the ever-increasing number of coronavirus cases globally. And Brexit…. It’s easy to be a pessimist in these circumstances, but given the recent economic data is it possible to be too pessimistic? It is fair to say that economic data releases have recently surprised to the upside. UK GDP growth for instance, or the labour market and PMI data. In fact, this is not just a UK phenomenon. Bloomberg computes a surprise index for various countries, which provides a measure of how data actuals compare against consensus forecasts. The latest indices for various countries/regions are shown graphically below (a result above zero indicates an actual/set of actuals that exceeded the forecast and vice versa).

Surprise Indices (source: Bloomberg)

The unprecedented nature of national government’s response to the pandemic made it difficult for economists to forecast economic outcomes. Interestingly, the overly optimistic projections for China at the start of the global pandemic possibly influenced the expectations for UK and US data, which have consistently exceeded forecasts. However, there was clearly some misplaced optimism about the Euro Area, although, as noted above, more recently it is economists that have been too pessimistic as lockdowns have eased and economic recoveries taken hold.

For more developed economies, economists possibly underestimated the how easily modern technology allows effective homeworking or spending on both household items during a lockdown. The importance of job protection schemes such as furlough cannot be stated strongly enough, and this helped economies remain afloat despite the circumstances.

While perhaps coincidental, government bond yields have risen in tandem over the past few days, suggesting investors are reassessing interest rate expectations on the back of the better data. The UK government 10-year bond yield is now touching the heady heights of 0.25%, up 15bps since last week.

No-one has ever accused me of being an optimist, so it will come as no surprise that the data has not changed my outlook. Considering the prospects for a second coronavirus wave (despite vaccines), the on-going need for social distancing measures, the likely rise in unemployment post furlough and the general undertone of public unease, and the sheer size of the reduction in output (the UK economy in particular) that needs to be recovered, it is difficult to be positive. During the financial crisis there was talk of the credit crunch being over by the end of 2017, but we hadn’t seen anything yet. Unfortunately, this has the same feel.

In a previous Insight I noted that the Bank of England appeared to be more optimistic simply because the data had beaten their illustrative scenario, though the Bank presented that scenario because it could not create any other usable forecasts. Most outcomes look positive against the worst-case scenario. Given the headwinds the UK is pushing into, I doubt we’ll be changing our economic projections any time soon.